Nikolai Vavilov: The Father of Genebanks

10 January 2024

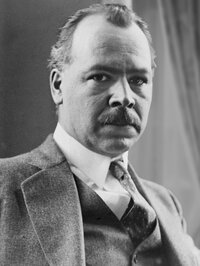

In this first installment of our Seed Heroes series, we celebrate the life and work of Russian scientist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov, known as the ‘father of genebanks' . Without his monumental achievements, plant conservation would be completely different.

Genebanks, germplasm collecting expeditions, and the use of plant genetic resources in breeding—albeit obscure terms to many—are now standard components of our food system thanks to pioneers like the Russian agricultural scientist Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov.

Vavilov imagined a world without famine. How would he make this happen? With the help of resilient plants that could withstand any environment.

As a geneticist, breeder and biologist in the early days of the Soviet Union, he became one of the greatest contributors to crop diversity conservation and use in history, redefining the field of botany along the way. A tireless traveler, Vavilov made 115 research expeditions to 64 countries on five continents to collect plant diversity and listen to farmers’ views on crops. He left an enduring legacy by establishing the first genebank of global significance, paving the way for other seed collections across the world in the decades that followed. This now seems routine, but in those times it was ground-breaking.

“In the 1930s, he masterminded the principles that currently form the basis of the Plant Treaty and the Global Plan of Action,” Nikolay Dzubenko, then director of the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR), said in a 2017 interview. “But he did so much more. Vavilov was the first to address strategic tasks of establishing, conserving and studying genetic collections scientifically.”

Searching the Wild

Best known for his work on identifying centers of crop origin and diversity, Vavilov traveled to regions where the cousins of cultivated plants grew in the wild, and found places where the greatest variety of particular crops occurred. From his research, he proposed eight main centers of origin for crop plants, ranging from soybean in China through to potatoes in Latin America.

Armed with this knowledge, Vavilov postulated that the diversity of crop wild relatives could be the basis for future plant breeding, and made his research and seed collection available to the world. He made crops more resistant to diseases by crossing them with their more resilient wild relatives.

Origins

Nikolai Ivanovich Vavilov was born on 25 November 1887 in Moscow, into a family of prosperous merchants in the textile industry. One of seven children, Vavilov had a younger brother, Sergei, who became a distinguished physicist for his work on optics and luminescence and was president of the USSR Academy of Sciences under Stalin.

As a boy, Vavilov was interested in natural science and had his own herbarium. He studied plant physiology and pathology – with a focus on snails as pests – at the Moscow Agricultural Institute before conducting postgraduate work under the soil scientist Dmitri Prianishnikov.

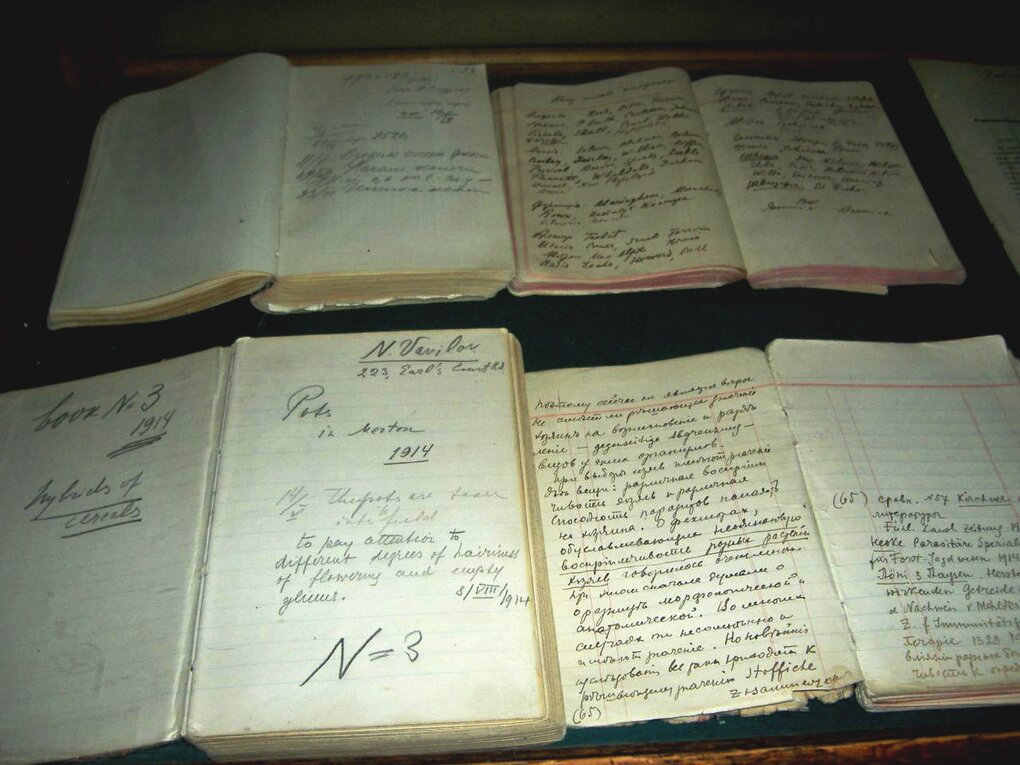

Vavilov began to work on selecting seeds for their resistance to disease in 1911 and continued his studies in England two years later at the John Innes Horticultural Institution (now the John Innes Centre). There, he worked with William Bateson, who coined the term “genetics” to describe the study of inheritance. Bateson also promoted the ideas of the German-Czech botanist Gregor Mendel, who proposed that some traits are passed on unchanged from generation to generation.

Revolutionary Botanist

In 1917, the year of the Russian Revolutions, Vavilov was appointed deputy head of the Bureau for Applied Botany, which later became Russia’s central institution responsible for the collection and conservation of global plant diversity. It is known today as the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR).

Vavilov was given increasing responsibility for overseeing the country’s agricultural research under Lenin and continued to establish the Soviet Union as a world leader in genetics and plant breeding after the Soviet leader’s death in 1924. He set up hundreds of research institutes and experiment stations across the huge country, building a staff that numbered more than 20,000.

Vavilov's notebooks at the N.I. Vavilov Institute of Plant Genetic Resources (VIR) in Saint Petersburg, Russia. Photo: Luigi Guarino

His fabled collecting expeditions began in 1916 in northern Iran and the Pamirs, and he returned to Russia with previously unknown varieties of wheat and rye. He continued to travel until 1933, making trips to the United States, China, the Latin American and Mediterranean countries, and Ethiopia.

Vavilov amassed more than 250,000 seed samples in his genebank, which became the world’s largest repository of crop diversity under his leadership. In World War II, the collection acquired legendary status during the 900-day siege of Leningrad, when the institute’s staff refused to eat the seeds even as they starved to death.

Political Nemesis

Vavilov’s lifelong mission to feed the nation through crop diversity began to unravel after Stalin’s forced collectivization program led to mass famine. In search of a solution, the Soviet leader endorsed the now discredited pseudo-scientific ideas of agronomist Trofim Lysenko, who undermined Vavilov’s position by attacking his Mendelian approach as bourgeois.

“We shall go into the pyre, we shall burn, but we shall not retreat from our convictions,” Vavilov famously said.

He was arrested in 1940 during a collecting expedition in western Ukraine and was formally accused of being a traitor and a British spy. His death sentence was later commuted to 20 years’ imprisonment.

Vavilov died in incarceration in Saratov on 26 January 1943. The cause of death was starvation: a bitter irony for one of the most prominent champions of food security in the 20th century.

Vavilov's Timeline

- 1887: Born in Moscow

- 1913-14: Studies plant genetics in the U.K. under William Bateson

- 1916: First seed expedition (Iran and Pamirs)

- 1917: Appointed deputy head of the Bureau for Applied Botany (later VIR)

- 1918: Professorship at Saratov University

- 1919: “The Theory of Immunity of Plants to Infectious Disease” is published

- 1926: “The Centers of Origin of Cultivated Plants” is published

- 1930-35: President of V.I. Lenin All-Union Academy of Agriculture

- 1930-40: Director of the Institute of Genetics

- 1940: Arrested by Stalin’s secret police on charges of spying for Britain

- 1943: Dies of starvation in prison in Saratov