Otto Frankel: 1960s Trailblazer for Plant Biodiversity Conservation

15 July 2024

In this installment of the Seed Heroes series, we commemorate the life of Otto Frankel, the Austrian-born scientist who pioneered the genetic resources conservation movement later in life after a prominent career as a plant breeder, geneticist and administrator in the Southern Hemisphere.

Sir Otto Frankel. Photo: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)

Few scientists would claim to have done their best work in retirement.

Yet Otto Frankel was one of them. The Austrian-born agriculturalist saved his most celebrated scientific achievements for the sunset years of his long and illustrious life.

For more than four decades, Frankel built a successful career that began in Europe, blossomed in New Zealand—where he spent 22 years—and officially ended in Australia when he stepped down as executive member of the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) at age 65.

While his time in the Southern Hemisphere included significant contributions to institution building for plant breeding research, and to the creation of new wheat strains in New Zealand, he viewed these years as secondary to his later mission.

“As I look back at my life, none of this was really outstanding or as important as the work on genetic resources, most of which came after I formally retired,” he said in a 1993 interview. “I look on the work we did on genetic resources and the genetics of conservation as my main contribution.”

After a knighthood in 1966, the retired plant breeder, geneticist and administrator embarked on a crusade that he would continue for more than 30 years: to help conserve rapidly disappearing plant biodiversity in the wild and in farmers’ fields.

His activism in the mid-1960s and early 1970s brought about a new global awareness of biodiversity loss and spurred governments to chart their own course of action.

Agriculture Meets Biodiversity

As consultant to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), Frankel spearheaded efforts to integrate FAO activities with the International Biological Program (IBP) on biodiversity. This resulted in a landmark 1967 conference to promote the exploration, conservation and use of plant genetic resources.

Frankel, who was chairman of the IBP/FAO Panel of Experts, used this occasion to coin the terms “genetic resources” and “genetic erosion” in collaboration with FAO scientist Erna Bennett. Together, they co-authored an influential book on the conference and dedicated it to legendary Russian agronomist Nikolai Vavilov, who had hosted the young Austrian scientist on a weeklong trip to Leningrad in 1935.

“Throughout the late sixties and early seventies, it was the Panel of Experts under Otto's activist chairmanship, and Erna Bennett within FAO, who kept the genetic resources issues alive,” L.T. Evans wrote in a 1999 memoir.

Frankel called for the establishment of a network of regional genetic resource centers and a coordination hub to recommend priorities and organize training. The proposal was presented to the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), which set up the International Board for Plant Genetic Resources (IBPGR) in 1973.

The IBPGR later became part of Bioversity International, which established the Crop Trust in 2004 on behalf of CGIAR and FAO.

Turning Point

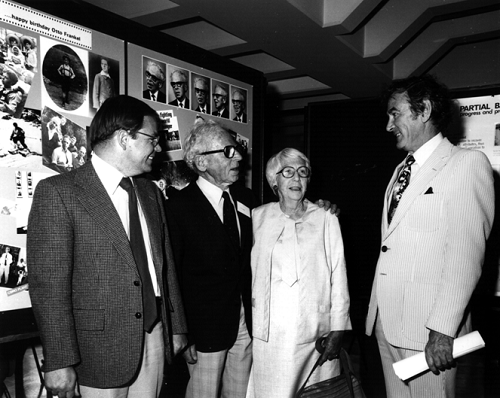

Left to right: Jim Peacock (Chief CSIRO Plant Industry), Sir Otto Frankel; his wife Margaret; Lloyd Evans, (former colleague and former Chief CSIRO Plant Industry) at Sir Otto’s 80th birthday celebration at CSIRO Plant Industry in 1980. Photo: Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)

Increasingly regarded as a spokesman for biodiversity conservation, Frankel addressed the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment, the first UN conference to focus on international environmental issues. The delegates in Stockholm adopted Frankel’s recommendations, and the topic captured global media attention.

“The genetic conservation wave began to roll, fourteen years before the term 'biodiversity' was coined,” according to Evans’s memoir.

Frankel published some ground-breaking papers during his ‘retirement’ years and claimed that humans needed to develop evolutionary ethics to reduce their impact on genetic variation. This was the subject of his Macleay Memorial Lecture in 1970 and a seminal paper on genetic conservation presented at the 13th International Congress of Genetics in Berkeley, California, in 1973.

“No longer can we claim evolutionary innocence,” he said in his 1970 lecture. “We are not the equivalent of an ice age or a rise in the sea level: we are capable of prediction and of control. We have acquired evolutionary responsibility.”

A book published with Michael Soulé in 1981 on conservation and evolution was also considered one of his best works, addressing the topic in a broader context.

Career Path

Otto Herzberg Frankel was born on 4 November 1900 in Vienna. His father was a barrister, and his mother’s family had several rural estates in Galicia, eastern Europe. He acquired his interest in agriculture during boyhood visits to his aunt’s estate, according to a 1998 obituary.

After attending universities in Vienna, Munich and Giessen, Frankel earned his doctorate in agriculture from the University of Berlin in 1925. He then spent two years as a plant breeder on a private estate near Bratislava, Czechoslovakia, before joining a team of scientists in Palestine to establish a plant and animal breeding program.

In 1928, Frankel’s next post took him to the Plant Breeding Institute in Cambridge, U.K, where he would stay only briefly before heading to New Zealand to accept a job offer.

At Lincoln College, near Christchurch, Frankel worked as a plant breeder and geneticist and later served as director of the Wheat Research Institute. After divorcing his first wife, Mathilde, and then marrying a local artist, Margaret Anderson, he left New Zealand in 1951.

Frankel spent the last 15 years of his formal career at the CSIRO in Canberra, Australia, where he was head of the plant industry division, transforming it into a modern scientific institution and campaigning for the construction of a phytotron, an iconic building with enclosed glasshouses used to study the environmental effects on plants.

His drive for a national facility of this kind culminated in the phytotron’s official opening by Prime Minister Robert Menzies in 1962—by which time Frankel had joined the CSIRO Executive—and set the stage for decades of world-leading plant research.

His enduring legacy is remembered at the entrance to the controlled environmental laboratory, which bears Frankel’s own words of warning: “Cherish the earth, for man will live by it forever.”

Timeline:

- 1900: Born on 4 November in Vienna, Austria

- 1925: Doctorate in agriculture at University of Berlin

- 1925‒26: Wheat breeder in Bratislava, Czechoslovakia

- 1927: Plant and animal breeding program, Palestine

- 1928: Plant Breeding Institute, Cambridge, U.K.

- 1929‒41: Plant breeder and geneticist, Lincoln College, New Zealand

- 1937: Divorces first wife, Mathilde

- 1939: Marries second wife, Margaret Anderson

- 1942‒49: Director, Wheat Research Institute, New Zealand

- 1950‒51: Director, Crop Research, Department of Scientific and Industrial Research, New Zealand

- 1951‒62: Chief, Division of Plant Industry, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia

- 1966‒94: Honorary Research Fellow, Division of Plant Industry, CSIRO, Canberra, Australia

- 1967: FAO conference on exploration, utilization and conservation of plant genetic resources

- 1970: Sir William Macleay Memorial Lecture on evolutionary responsibility

- 1972: Addresses UN Conference on the Human Environment, Stockholm

- 1973: Paper presented at the 13th International Congress of Genetics in Berkeley, California

- 1981: Publishes book Conservation and Evolution with Michael Soulé

- 1995: Co-writes book The Conservation of Plant Biodiversity with A.H.D. Brown and J.J. Burdon

- 1998: Dies on 21 November at age 98 in Canberra, Australia

Image sources:

- Top banner: Australian Academy of Sciences

- Body images: The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO)

Categories: For Educators, For Students